The switch-off of the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) marks a definitive end to an era where telephony was physically tethered to geography. For decades, a copper wire offered an implicit guarantee. If the line had a dial tone, emergency services knew exactly where you were.

That certainty has evaporated.

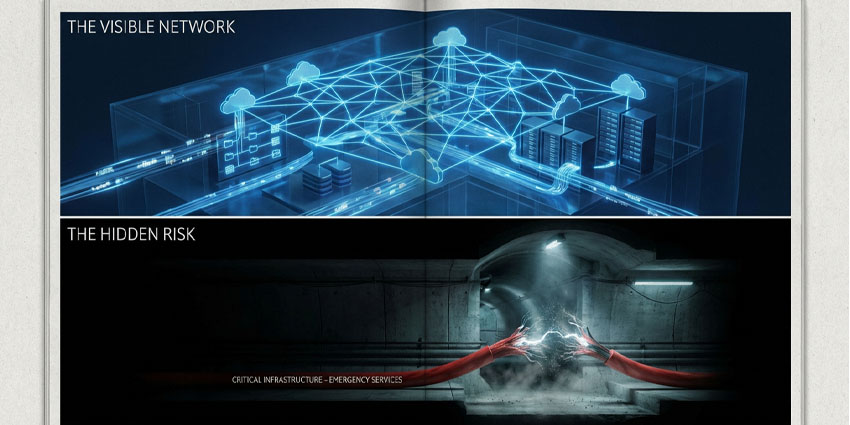

As organizations migrate to IP voice and Unified Communications as a Service (UCaaS), they are trading hard-wired reliability for digital flexibility. Yet, this transition has exposed a critical vulnerability in enterprise architecture. In the fluid topography of hybrid work, emergency calling has ceased to be a simple feature of telecommunications and has mutated into a rigorous engineering discipline.

The danger lies in the invisibility of the risk. Modern UC platforms are remarkably robust for day-to-day collaboration, lulling organizations into a false sense of security. A video meeting may function perfectly even when the underlying signaling path for an emergency call is severed, or, worse, misrouted. This disconnect creates a scenario where the failure is only realized during a crisis.

As Alex Kugell, Chief Technology Officer at Trio, trenchantly observed to UC Today, the nature of the obligation has fundamentally shifted:

“In an IP voice world, emergency calling becomes a systems problem, rather than a telecom problem.”

On one level, it’s a technical migration. On a deeper level, however, it’s also a transfer of liability. The assumption that cloud providers inherently manage the granular complexities of local survivability is a dangerous oversight. Without deliberate architectural intervention, the shift to the cloud can quietly introduce points of failure that the legacy PSTN never possessed.

- Microsoft Teams Phone PSTN Users Surges to 26 Million, up 30% in 20 Months

- BT Group Delays PSTN Switch Off

The Location Paradox After the PSTN Switch-Off: When Site No Longer Equals Address

The most immediate casualty of the shift to cloud voice is the concept of a static user. In the legacy model, a phone number was a proxy for a desk. Today, a user is a digital identity that floats between headquarters, a home office, and a coffee shop, often within the span of a single day.

This mobility breaks the fundamental logic of traditional emergency dispatching. If the network cannot dynamically track the movement of a softphone or a hot-desking endpoint, the “dispatchable location”, the specific building, floor, and room information required by first responders, becomes obsolete the moment an employee stands up.

The discrepancy between a functional endpoint and accurate location data is often wider than IT leaders anticipate. It is a logistical nightmare that requires synchronizing disparate datasets, such as HR records, facilities management, and network topology.

Kugell highlighted the granular necessity of this data, arguing that generic site addresses are insufficient in large enterprise environments. “Location accuracy is another major risk. Site no longer equals address,” he explained. “When the call reaches 911, it must include a dispatchable location, which means the location must be defined precisely enough that first responders know where to go.”

The operational reality, however, suggests that many enterprises are failing to maintain this precision. When location data is treated as a “set and forget” configuration during the initial migration, it degrades rapidly.

Matt Beucler, CEO and Founder of Plura AI, with 20+ years of experience across telephony and contact center technology, cited data to UC Today suggesting that the entropy of location accuracy is severe:

“Teams often rely on static location mapping, which does not work in dynamic environments. In reviewing these projects, we found that six months after day-one deployments that technically met E911 requirements, 30 to 40 percent of users had a bad dispatchable location.”

This statistic serves as a stark indictment of current maintenance practices. A thirty percent failure rate in a life-safety system is absolutely untenable. The challenge is that the tools used to manage this, including static spreadsheets or one-time database uploads, are incompatible with the fluid nature of modern work.

Ownership needs to be clearly defined among IT, facilities, security, HR, and others, and kept up to date as people hot-desk or move about the office. Without automated, real-time validation, the enterprise is effectively operating blind.

Engineering Survivability: The Fallacy of Healthy Voice

Resilience in the IP world is a deceptive concept. In a PSTN environment, the phone lines often carried their own power. In a VoIP environment, the dependency chain is long and fragile, relying on the Local Area Network (LAN), the Wide Area Network (WAN), the Internet Service Provider (ISP), and the building’s power supply. A failure at any link in this chain can isolate a facility, even if the cloud platform itself is fully operational. This is the distinction between service availability and site survivability.

Organizations frequently conflate the health of their UCaaS tenant with the ability to make an emergency call. However, the path a 911 call takes is distinct and requires specific routing logic that bypasses standard least-cost routing or internal dial plans.

Kugell argued that failures in this domain are rarely the result of mysterious technical glitches but rather of architectural oversight. “These emergency calling failures result not from technology outages but from flawed design assumptions,” Kugell outlined. “You can therefore expect in a real event where voice may seem healthy, but calls fail because of how location errors, routing mistakes, or ownership gaps should be addressed in new ways.”

To mitigate this, architects must design for degradation. This involves engineering failover paths that activate instantly when primary connections are severed. It requires a “belt and suspenders” approach that assumes the primary ISP will fail or the main trunk will be saturated. True resilience is active, not passive. Kugell asserted:

“Resilience means engineered survivability. Local calling fallback, multi-carrier routing, battery-backed infrastructure, and mobile failover paths that are validated under degraded conditions.”

The reliance on the public internet for critical signaling adds another layer of unpredictability. Unlike a dedicated circuit, the internet offers no Quality of Service guarantees. In the event of a regional power outage or ISP brownout, the ability to reach a Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) can be compromised just when it is needed most. Live failover testing and evacuation drills may misroute calls to the wrong dispatch center, drop calls when signaling paths are blocked, or provide incorrect caller identity.

Designing for these scenarios requires simulating them (pulling the plug, quite literally) to see whether the backup cellular gateway engages or whether the local gateway successfully routes the call to the PSTN.

The Compliance Gap: The Myth of Vendor Responsibility

Perhaps the most pervasive risk in the transition to cloud voice is the assumption of transferred compliance. There is a tacit belief among many tech buying committees that by signing a contract with a global UCaaS provider, they have outsourced their regulatory obligations regarding E911 and Kari’s Law. This is, in many cases, a legal and operational fiction. While vendors provide the technical capability to transmit location data, the responsibility for the accuracy of that data and the configuration of the system rests squarely with the enterprise more often than not.

Naturally, regulatory frameworks vary significantly by region, and the nuances of these obligations are often lost in global deployment strategies. When a US-based directive is applied to a European office, or vice versa, the result is often a compliance gap that leaves the organization exposed.

Beucler identified this misplaced confidence as a primary source of risk. “With decades of experience working with call centers, telephony, and UC platforms, I’ve found that the most common compliance blind spot I encounter during a cloud voice migration is when teams assume that emergency calling compliance transfers automatically to the new vendor. It doesn’t,” Beucler warned.

The disconnect stems from a lack of clear internal ownership. Emergency calling sits in an uncomfortable organizational gray zone. It is part IT, part legal, and part physical security. Without a single executive owner, the system’s maintenance falls through the cracks. The contract may be signed, but the operational runbooks may never be written.

Beucler emphasized that the cloud model does not absolve the customer of the “last mile” of data integrity. “The customer is ultimately still responsible for accuracy of location data, endpoint configuration, and ongoing validation,” he noted. ”

What I wish more organizations had required sooner, however, is a single owner of the location-data lifecycle who regularly validates it, documents it for audits, and tests for compliance whenever anything changes.”

The consequences of this negligence are substantial. Regulatory fines are one thing, but lasting reputational and existential damage are quite another. In an era where corporate duty of care is scrutinized, the inability to support a basic emergency call is a defenseless position.

The biggest compliance gaps occur when regional obligations are either misinterpreted or go unspoken and are relegated to vendors. Organizations must audit their contracts and architectures to ensure that the line of responsibility is clearly defined and that compliance is treated as a continuous process, not a checkbox on a migration project plan.

So… What Can You Actually Do About It Ahead of the PSTN Switch-Off?

The transition from the PSTN to the cloud is inevitable and beneficial, but it demands a recalibration of how we view critical infrastructure. We have moved from a world of hardware guarantees to one of software probabilities. In this new paradigm, emergency calling cannot be treated as a legacy feature that will simply take care of itself. It requires active design, rigorous testing, and clear governance.

As the perimeter of the enterprise dissolves into the hybrid workspace, the safety net that the PSTN once provided is gone. It must be rebuilt, code line by line, by IT leaders who understand that in a crisis, the network is the only lifeline that matters. The technology exists to make cloud voice as safe, if not safer, than the copper lines it replaces. But technology without architecture is merely potential. The imperative now is to stop assuming the phone will work and start engineering the certainty that it will.