France is moving to make videoconferencing part of its sovereign infrastructure, and will bin the likes of Microsoft Teams, Zoom Workplace, GoTo Meetings, and Cisco Webex in the process.

The government has announced the generalization of “Visio,” a secure videoconferencing tool developed by the Interministerial Digital Directorate (DINUM), intending to roll it out across all state services by 2027 and reduce reliance on non-European platforms.

The French government argues that public administrations have come to rely on a patchwork of UC and collaboration tools that increase security exposure, add cost, and complicate cooperation between ministries. France’s preferred remedy is to standardize on a state-controlled option built on French technologies, as part of a broader effort to strengthen “digital resilience.”

Notably, the press release highlights that these tools belong to businesses that are “non-European.” Although the French government has been developing and testing Visio for roughly a year, the timing seems particularly conspicuous amid escalating trade tensions between Europe and the US under the Trump administration.

David Amiel, Minister for the Civil Service and State Reform, commented:

“The aim is to end the use of non-European solutions and guarantee the security and confidentiality of public electronic communications by relying on a powerful and sovereign tool.”

Visio began as an experiment about a year ago and already has 40,000 regular users, with deployment now extending to 200,000 agents, according to the press release. The CNRS, Health Insurance, the General Directorate of Public Finances (DGFiP), and the Ministry of the Armed Forces are among the first administrations slated to generalize the solution in the first quarter of 2026.

France is also positioning Visio as a security-led platform with modern collaboration features rather than a minimalist replacement. The press release says Visio is deployed with support from ANSSI, hosted on sovereign infrastructure labeled SecNumCloud at Outscale (a Dassault Systèmes subsidiary). It includes AI meeting transcription using speaker separation technology from French startup Pyannote, with real-time subtitling planned for summer 2026 using technology from French AI research lab Kyutai.

The government is also touting cost savings: the press release estimates €1 million in savings per year for every 100,000 users who move off paid licenses.

“We cannot take the risk of seeing our scientific exchanges, our sensitive data, our strategic innovations exposed to non-European players,” Amiel added. “Digital sovereignty is both an imperative for our public services, an opportunity for our companies, and an insurance against future threats.”

Market and Geopolitical Analysis of France’s Visio Move: Could Europe’s “Sovereignty” Push Also Be a Hedge Against a Volatile America?

France’s move fits a broader European arc of digital sovereignty as a response to technical risk, regulatory pressure, and an increasingly geopolitical technology supply chain. But the current moment adds a sharper edge. Under President Donald Trump, America’s posture on trade and alliances has become less predictable, and Europe’s response is increasingly looking less like rhetorical posturing and more like portfolio reallocation, with some nations turning away from dependence on US infrastructure, US platforms, and, in some cases, US assets.

That shift is showing up in financial markets as well as in technology policy. In Sweden, pension fund Alecta told Reuters it has sold most of its US Treasuries over the last year because of “the increased risk and unpredictability of U.S. politics,” adding that reductions since the beginning of 2025 account for “the majority” of its holdings. In Denmark, AkademikerPension said it is exiting US Treasuries, citing concerns about US government finances, and noted the move comes amid escalating tensions over Trump’s threats regarding Greenland. CNBC reported the fund planned to close a position of around $100 million in US Treasuries by the end of the month.

The largest institutions are also being watched for signs of a longer-term trend. Reuters reported that the market value of US Treasuries held by Dutch pension fund ABP, Europe’s largest, dropped sharply from December 2024 to September of the following year, “another sign that major European investors have grown more cautious around holding US assets.”

The connection to enterprise technology is far less abstract than it might initially appear. Capital markets are, in effect, pricing a narrative of geopolitical uncertainty, fiscal strain, and policy volatility. Tech leaders, meanwhile, are being asked to price the same uncertainty into vendor strategy: where data sits, which jurisdiction governs it, and how quickly an organization can keep operating if a supplier relationship becomes politically or legally fraught.

France’s Visio decision is an obvious example because it treats videoconferencing as a form of national infrastructure, and it’s not the only example of a European government organization electing to move away from the global UC&C titans.

Last summer, both Danish and German government bodies announced they were pivoting away from Teams due to similar “digital sovereignty” concerns. In September, several Dutch ministries began reconsidering their reliance on Microsoft Teams amid fears of a strategic dependence on American technology platforms.

What France Ditching Zoom and Microsoft Teams Could Mean for Tech Buyers: Rethinking your UC Risk Model

For the vast majority of enterprises, Visio is not an option for procurement; the Suite Numérique tools are reportedly intended for civil servants, not for public or private company use in France. The lesson is not a vendor recommendation but a procurement signal.

First, the center of gravity in UC buying is moving. Feature parity still matters, but in regulated industries and in globally exposed companies, the next competitive differentiator is increasingly governance: demonstrable control over meeting data, clarity on lawful access and jurisdictional exposure, and resilience planning that assumes disruption, whether technical, legal, or political.

Second, enterprises should expect “sovereignty-flavored” questions to migrate from government into the private sector via customer requirements and supply-chain audits. The “who can compel access to what” question, once mostly the domain of public-sector security offices, is becoming relevant to any company doing business with governments, defense-adjacent supply chains, critical infrastructure operators, or heavily regulated financial and healthcare ecosystems.

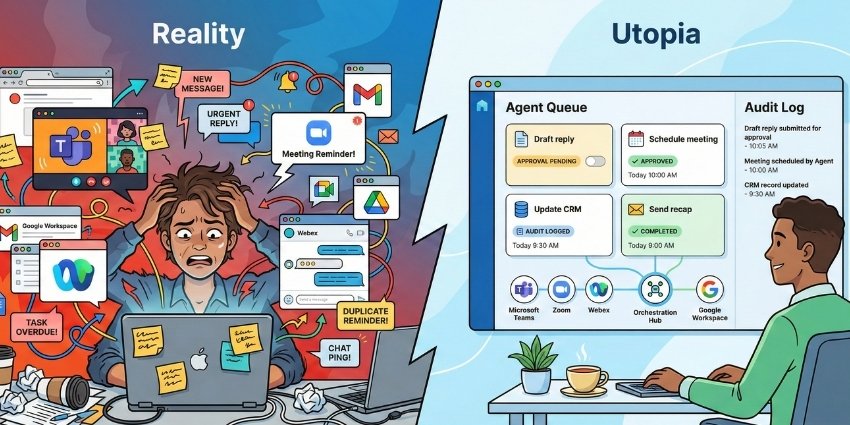

Finally, France’s approach spotlights a hard truth that IT leaders sometimes understate in board conversations: consolidation is not just a cost play. It is also a control play. If your organization is running three or four meeting platforms across business units, the complexity is not merely annoying—it can become the weak point in governance, retention, eDiscovery readiness, and incident response. France is arguing, in effect, that collaboration sprawl is a strategic dependency, and dependency has a habit of becoming expensive at precisely the wrong moment.