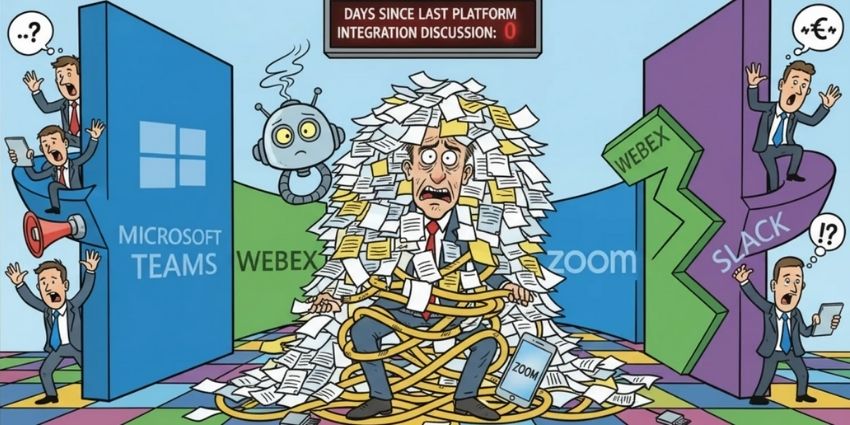

I’ve been thinking about something rather odd lately. For years, we’ve been watching UC vendors build ever-higher walls around their platforms. Microsoft wants you living entirely in Teams. Zoom wants to be your everything. Cisco insists Webex is all you need. Meanwhile, the rest of us have been cobbling together workarounds, copying messages between platforms, and maintaining separate presence indicators like we’re running multiple personalities.

But here’s the thing. We’re nearly in 2026, and this situation has become rather untenable.

The Microsoft Teams Reality

Perhaps we should start with the elephant in the room. According to IDC, 45.6% of the global UC&C market now belongs to Microsoft. Nearly half. That’s not just market leadership, it’s approaching dominance.

You get the sense that this changes everything about the conversation. When one vendor controls almost half the market, the battle is no longer just about features. It’s about ecosystems. About whether the industry will consolidate around a single platform or fragment into walled gardens that occasionally acknowledge each other’s existence.

Microsoft has achieved this position through a rather clever strategy. They didn’t just build a better mousetrap. They bundled Teams with Office 365, made it nearly free for existing customers, and integrated it so deeply into the Microsoft ecosystem that extracting it would require organizational surgery.

It worked. Brilliantly. And now we’re left with an interesting question:

What happens when half the market lives in one vendor’s ecosystem while the other half is scattered across competitors?

The Walls We’ve All Built

Walk into most organizations today, and you’ll find something rather messy. Marketing uses Slack because that’s where their workflows evolved. The development team insists on their own tools. Sales lives in Zoom because that’s what customers know. Corporate IT has deployed Microsoft Teams, which everyone uses for some things, sometimes, when they remember.

And between all these platforms? Walls. Tall ones. With barbed wire on top.

It’s a bit like expecting everyone in London to only ride the Tube and never take a bus. Logical from Transport for London’s perspective, perhaps, but completely ignoring how people actually move through a city.

The problem is that these walls aren’t accidental. They’re deliberate architectural choices designed to keep users trapped within specific ecosystems. Microsoft wants you to use Teams for everything. Zoom wants to be your complete collaboration platform. Slack insists it’s the hub for all your work.

And when one vendor controls 45.6% of the market, those walls become particularly expensive for everyone else.

What These Walls Actually Cost

I began to wonder what all this platform separation actually costs organizations. Not in licensing fees, though those are substantial enough. But in something harder to measure and far more expensive.

Consider this scenario, which happens thousands of times daily across the business world: you’re collaborating with your team in Slack when someone needs to bring in a client. But the client only uses Teams. So you schedule a separate Teams meeting, manually copy the conversation context, and spend the first ten minutes of the call re-establishing what’s already been discussed. By the time everyone’s caught up, you’ve burned thirty minutes and three people’s attention spans.

Or here’s another: your calendar shows you’re available because your company uses Outlook, but you’re actually presenting at a Webex session that the scheduling system doesn’t know about. A colleague calls you during your presentation. You look unprofessional. They feel awkward. Everyone loses.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re the daily texture of modern work. And they’re entirely artificial problems created by vendors who profit from keeping users trapped within their ecosystems.

When Microsoft controls nearly half the market, these problems become even more acute. You can’t simply avoid Teams anymore. Your clients use it. Your partners use it. Your new hires expect it. But you might have perfectly good reasons for using other platforms too.

The walls don’t just inconvenience you. They actively make collaboration harder with nearly half the business world.

The Simple Truth About 2026

We’re nearly in 2026. The technology to solve these problems has existed for years. APIs, federation protocols, presence standards. None of this is remotely difficult from a technical standpoint.

What’s been missing is will. Vendors have been quite comfortable with the status quo because lock-in works brilliantly as a business model. Why make it easy for customers to use competing platforms when you can force them to choose?

But something’s shifting. Perhaps it’s regulatory pressure, particularly in Europe where interoperability is becoming a compliance requirement. Perhaps it’s simply that customers are tired of paying premium prices for platforms that actively make their lives harder.

Or perhaps it’s that when one vendor controls 45.6% of the market, the competitive dynamics change. Smaller players can’t compete on ecosystem lock-in anymore. Microsoft has already won that battle. The only viable strategy for everyone else is to make interoperability so seamless that platform choice becomes about features and value rather than which ecosystem you’re imprisoned within.

Microsoft and Zoom have already demonstrated basic calling federation. It works. Users can click a button in Teams and connect to someone on Zoom without switching applications or creating separate accounts. The technical barriers are gone. Only the business incentives remain.

And increasingly, those business incentives are pointing toward openness. Because in a market where Microsoft owns half the conversations, everyone else needs to make it easy to talk to that half.

What Open Doors Actually Means

Let me be clear about what I’m suggesting here. Not some complicated middleware solution or elaborate integration architecture. Just platforms that fundamentally respect that users exist across multiple systems and make that reality work smoothly.

Imagine clicking a contact in Slack and choosing whether to call them via Teams, Zoom, or Webex, depending on where they happen to be available. The system handles the connection automatically. No separate apps. No copying meeting links. Just a call.

Or picture your presence indicator reflecting your actual status across every platform you use. You’re in a Zoom meeting, so your status shows busy in Teams, Slack, and Webex simultaneously. Simple. Obvious. Currently impossible without manual updates.

Shared calendars that understand multi-platform work realities. Federated calling that treats platform boundaries as routing decisions rather than impassable borders. Presence that actually reflects presence rather than which application happens to be open.

None of this requires revolutionary technology. It just requires vendors to stop treating other platforms as mortal enemies and start treating them as adjacent neighborhoods in the same city.

In a world where Microsoft controls 45.6% of that city, this becomes essential rather than optional. You can’t wall yourself off from half the market and expect to thrive.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

There’s something deeper going on here beyond mere technical convenience. The current platform separation fundamentally limits how organizations can adapt to changing work realities.

Right now, choosing a UC platform feels permanent. You’re committing to an ecosystem, retraining staff, rebuilding workflows. The switching costs are so high that most organizations stick with suboptimal choices for years longer than they should.

But if platforms actually connected properly? You could use the best tool for each job without worrying about interoperability. Sales could stay in Zoom because that’s where their customers are. Development could use whatever collaboration tool works best for their workflows. Corporate functions could standardize on Teams for policy compliance.

And critically, none of these choices would wall off parts of your organization from each other or from the 45.6% of the market living in Microsoft’s ecosystem.

This would be rather good for productivity, one suspects.

The ecosystem battle is essentially over. Microsoft won. The question now is whether we’ll have one massive walled garden with several smaller ones scattered around it, or whether we’ll finally build the bridges that let people move freely between them.

The Regulatory Push

I should mention that vendors may not have much choice in the matter soon. The EU’s Digital Markets Act is already forcing major platforms to open up their messaging systems. Similar regulations are being discussed in the UK and US.

The European Commission has made its position clear. Large communication platforms will need to offer interoperability. Not as a nice-to-have feature but as a legal requirement.

Microsoft, Meta, and Google are already adapting their messaging platforms to comply. It seems reasonable to expect UC platforms to follow.

The question isn’t whether walls will come down but how gracefully vendors handle the transition.

Some will resist, obviously. There will be claims about security concerns and technical complexity and user experience degradation. Most of these will be rather transparent attempts to preserve lock-in business models.

But the direction seems clear. When you control 45.6% of the market, regulators start paying attention. And they’ve decided that level of market concentration requires interoperability safeguards.

By 2026, platform isolation will increasingly look like a choice rather than a technical necessity. And customers will remember which vendors chose openness and which ones had to be dragged there by regulators.

What Organizations Should Demand

So what does this mean for IT leaders and decision makers trying to plan for 2026 and beyond?

First, stop accepting platform isolation as normal. When vendors claim their platform doesn’t integrate with competitors, ask why. The technical barriers are largely gone. What remains are business decisions that work against customer interests.

Second, make interoperability a requirement in procurement. Not vague promises about APIs that might exist somewhere but actual demonstrated capability to federate calls, share presence, and connect users across platforms. If a vendor can’t show this working today, that tells you everything about their priorities.

Third, prepare your organization for a genuinely multi-platform future. Stop trying to force everyone onto a single system. Focus instead on ensuring your users can work effectively regardless of which platform they’re using at any given moment. In a world where Microsoft controls nearly half the market, multi-platform reality is unavoidable.

Fourth, support regulatory efforts toward interoperability. The vendors won’t do this voluntarily. They’ll need encouragement. Rather firm encouragement, probably.

The Slightly Awkward Reality

I suppose what I’m really suggesting is that we’ve wasted years on a false problem. The industry has obsessed over which platform will “win” when the actual question should have been how to make all platforms work together properly.

Microsoft has won the market share battle. 45.6% is a decisive victory by any measure. But that doesn’t mean they’ve won the right to wall off nearly half the business world from everyone else.

It’s a bit like the charging cable debate between Lightning and USB-C. Everyone argued about which standard should win when the real solution was always to just adopt universal compatibility. Apple resisted for years until regulators forced their hand.

Now everyone’s phones charge with the same cable, and somehow the world kept turning. Eventually, that’s precisely what happened, but not before a lot of unnecessary conflict and customer frustration.

UC platforms are heading the same direction. The walls will come down because they must. The question is whether vendors embrace this transition or get dragged into it kicking and screaming.

By 2026, platform interoperability won’t be a competitive advantage. It will be table stakes. The minimum acceptable standard for any serious UC offering.

Vendors that understand this early will thrive. Those that cling to walled gardens will increasingly look like telephone companies in the early 2000s, desperately trying to charge for text messages while the internet made the whole business model obsolete.

The ecosystem battle is over. Now we need to make sure the winning ecosystem doesn’t become a gilded cage.

Ponder This

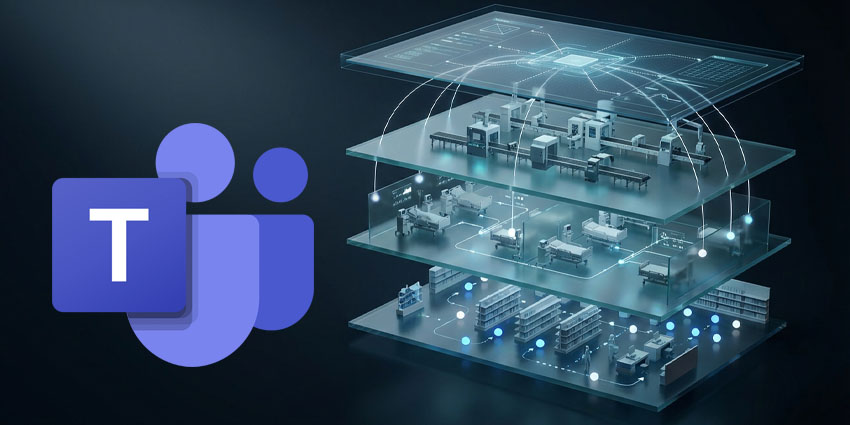

I wonder sometimes whether AI will be the thing that finally forces these walls down.

We’re already seeing AI agents scheduling meetings, AI assistants summarizing calls, AI copilots drafting messages. Within a year or two, we’ll have AI colleagues participating in brainstorms and AI customers placing orders through conversational interfaces.

And here’s the rather awkward bit. AI doesn’t care about vendor loyalty. An AI agent trying to schedule a meeting between a Teams user and a Zoom user won’t politely accept that these platforms don’t talk to each other. It will simply fail. And when your AI assistant fails to do basic tasks because of artificial vendor restrictions, that failure becomes rather visible and rather expensive.

You get the sense that legacy camps around voice and chat might not survive contact with AI reality. Because AI simply won’t work properly unless vendors open up their ecosystems to bots interacting with their stacks.

Imagine your AI assistant needs to check if someone’s available before scheduling a call. If presence information is locked inside Teams, unavailable to AI agents working across multiple platforms, the AI can’t function. It becomes a rather expensive glorified paperweight.

Or consider an AI customer service agent that needs to seamlessly hand off a text conversation to a voice call when complexity increases. If that handoff requires the customer to switch platforms or download new software, the experience breaks down entirely. The AI customer simply goes elsewhere.

The walled gardens that sort of work for human users become completely untenable for AI agents. Bots need clean APIs, standardized protocols, and seamless cross-platform operation. They can’t fudge their way through platform transitions the way humans reluctantly do.

Which means vendors face a rather stark choice. Open up their ecosystems to AI agents working across platforms, or watch as AI-powered competitors who did open up their systems simply eat their lunch.

Microsoft might control almost half of the UC market today. But AI doesn’t respect market share. It respects interoperability. And the first vendor to make their platform truly AI-agent-friendly across ecosystem boundaries might find they’ve got a rather significant competitive advantage.

The walls might not come down because humans demanded it. They might come down because AI simply won’t tolerate them. And vendors who don’t adapt will discover that controlling 45% of yesterday’s market means rather less than controlling 10% of tomorrow’s.

That would be quite something, wouldn’t it?

Continue the Conversation

Follow me on LinkedIn for more news and analysis.

Ready to discuss the future of UC interoperability? Join 2,000+ industry professionals in our UC Today LinkedIn community where we’re exploring what AI means for platform boundaries.

And don’t miss our weekly insights on the evolving unified communications landscape. Subscribe to our newsletter for the most crucial UC industry news delivered straight to your inbox.